ETSi professors discover a method for the mass production of microfibers

ETSi professors discover a method for the mass production of microfibers

Professors from the Department of Aerospace Engineering and Fluid Mechanics at the Higher Technical School of Engineering of the University of Seville have developed a method for the mass production of microfibers made from a polymer called polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). This study, published in the article https://doi.org/10.1039/D3RA03070A , represents a significant advance in the possibility of industrially producing nanofibers.

Professors Luis Modesto López and Alfonso Gañán Calvo, along with student Jesús Olmedo Pradas, present this new technology in the article, which can be applied to the mass production of micro and nanomaterials, particularly nanofibers. “Due to its high processing capacity, the technique we propose could, in the future, be scaled up and adapted to industrial production, thereby improving production rates. Furthermore, it should be noted that this is a technique for producing polymer fibers, and these materials are present in practically every aspect of daily life, making its application truly broad and diverse: manufacturing so-called biocompatible scaffolds for use in tissue regeneration, producing fibrous platforms for energy generation and storage systems (i.e., electrodes), and 3D printing systems. Other highly visible and currently relevant industrial applications include manufacturing materials for masks and PPE, or for so-called “smart wearables” (intelligent fabrics),” states Professor Modesto López.

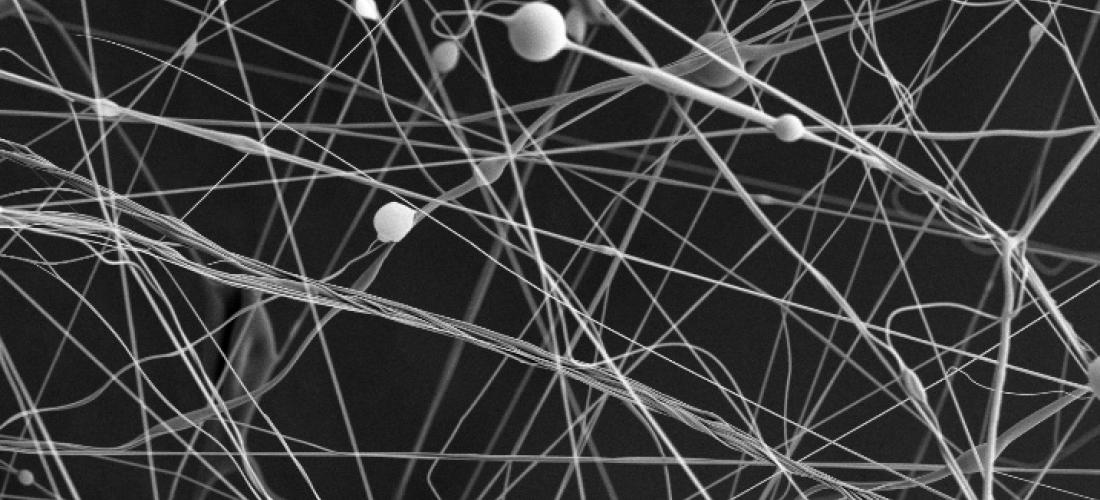

The significance of this work lies in the mass production of very thin fibers, known as microfibers, made from a polymer called polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). They use a unique process that, with a single injector, can process a thousand times more microfibers than conventional systems, such as electrospinning. These microfibers have a diameter of less than 1 micrometer (1 micron, one millionth of a meter), between 0.9 and 0.5 microns, meaning they are much thinner than a human hair (100 microns) or a red blood cell (8 microns). They can even be as thin as the coronavirus (less than 0.5 microns).

The study aimed to develop a simple yet robust technology for producing micro- and nanofibers using Flow Blurring® pneumatic injectors (provided by Ingeniatrics Tecnologías SL). These devices use an air stream to fragment a liquid flow, resulting in the formation of fine droplets (similar to those produced by patio sprinklers), a process known as atomization. It is important to note that our study was funded by the PAIDI 2020 and FEDER programs.

Professor Modesto López explains how they arrived at this discovery: “The research began with spraying experiments aimed at producing microdroplets. However, instead, we obtained elongated structures that we called ligaments. By studying the underlying physics of the spraying process, we realized that the ligaments formed when using highly viscous liquids with a certain degree of viscoelasticity. Nevertheless, a method was needed to solidify the ligaments and obtain fibers. Therefore, we used a heat source, in this case a tubular oven capable of reaching temperatures up to 1200 degrees Celsius, although 300 degrees was sufficient in our study. In short, we sprayed a polymer solution inside the oven using a flow blurring injector. The heat generated by the oven allowed the ligaments to dry rapidly, resulting in the formation of microfibers in a matter of seconds. Simultaneously, we performed computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations to better understand the physical processes governing the fragmentation of the polymer solutions.” and the formation of the ligaments.”.

Most of the work was carried out in the Fluid Mechanics laboratory, in the Department of Aerospace Engineering and Fluid Mechanics of the ETSI, although they also made use of the facilities of CITIUS, where they analyzed the viscosity of the polymer solutions in the Functional Characterization unit and examined the shape and size of the microfibers using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) of the Microscopy unit.

The project is transformative in that it aims to revolutionize conventional methods for producing micro- and nanofibers. Currently, the most common techniques for manufacturing nanofibers use electric fields as an energy source to "stretch" polymer solutions, reduce their size, and/or fragment them; however, this requires the liquid to have a certain degree of electrical conductivity. Furthermore, these techniques have a low processing capacity for the solution in question, on the order of 0.1 milliliters per hour. In this respect, our technology is more energy-efficient than current methods because it does not depend on an external energy source to fragment the liquid. Instead, it harnesses the mechanical energy contained in the airflow to generate new surface area, that is, a multitude of finer fibers. Likewise, the proposed technology has an extremely high processing capacity, as it can operate with liquid flow rates on the order of 1500 milliliters per hour, which is more than a thousand times the capacity of conventional systems. Furthermore, this project opens a new line of research related to the manufacture of composite fibers consisting of two or more polymeric materials and which in turn may contain functional nanoparticles or materials such as graphene and carbon nanotubes.